From Parking Lot to Midtown: Why North Hills Is the Right Place to Build Tall

A local history lesson on growth, delay, and the limits of saying “maybe later”

North Hills is one of Raleigh’s most visible examples of how cities actually change over time. It’s also one of the clearest lessons we have in how our planning system and political instincts shape what ultimately gets built.

In the 1960s, North Hills Mall opened as the first indoor shopping mall between Atlanta and Washington, D.C. It was a regional destination, anchored by department stores and surrounded by acres of surface parking. People drove long distances to shop there because that was the dominant model of retail at the time. The site was designed for a Raleigh organized around driving, single‑purpose trips, and the assumption that retail would continue to concentrate into large, centralized malls. By the late 90s, that model was breaking down. North Hills, like malls across the country, struggled with vacancies and declining consumer spending. What remained were large expanses of asphalt and aging commercial buildings that no longer matched how Raleigh lived, worked, or grew.

Beginning in the early 2000s, Kane Realty started redeveloping the site incrementally. Rather than clearing everything at once, the mall and surrounding strip retail were transformed piece by piece into a street network with apartments, offices, storefronts, and public spaces. This incremental approach has allowed North Hills to evolve in response to real demand while reusing land that was already paved and part of the city.

Urban planners have a name for this kind of transformation. Ellen Dunham‑Jones, whose work on Retrofitting Suburbia is the textbook on how cities should think about post-suburban growth, describes this process: taking failing malls and strip retail and incrementally transforming them into mixed‑use districts that absorb growth without pushing development farther outward.

North Hills’ evolution has been significant for nearby neighborhoods. For long‑time neighbors, living next to a growing urban district is very different from living next to a declining mall. It’s fair to acknowledge that disruption.

But it’s also important to be honest about the alternative. Very few people genuinely want to return to the days of empty Winn‑Dixie and JCPenney parking lots, adorned by lethargic strip retail. Even if you decry the recent uptick in traffic, the underused structures of years past generated traffic too, just without housing, stable jobs, or varied recreation attached to them. Much of the congestion on Six Forks Road today is regional traffic passing through the area from far‑out suburbs, not from trips created by people who live or work on the site.

If Raleigh is serious about putting height in the right places, North Hills is the obvious answer. It is underutilized commercial land that has already proven it can absorb density and function as a real urban center.

That history of successful redevelopment matters today, because North Hills is back before City Council with another rezoning request. Case Z‑34‑25 is about putting height where it actually makes sense. It’s also a test for how cities make decisions when good but imperfect projects come forward.

What’s on the table in Z‑34‑25?

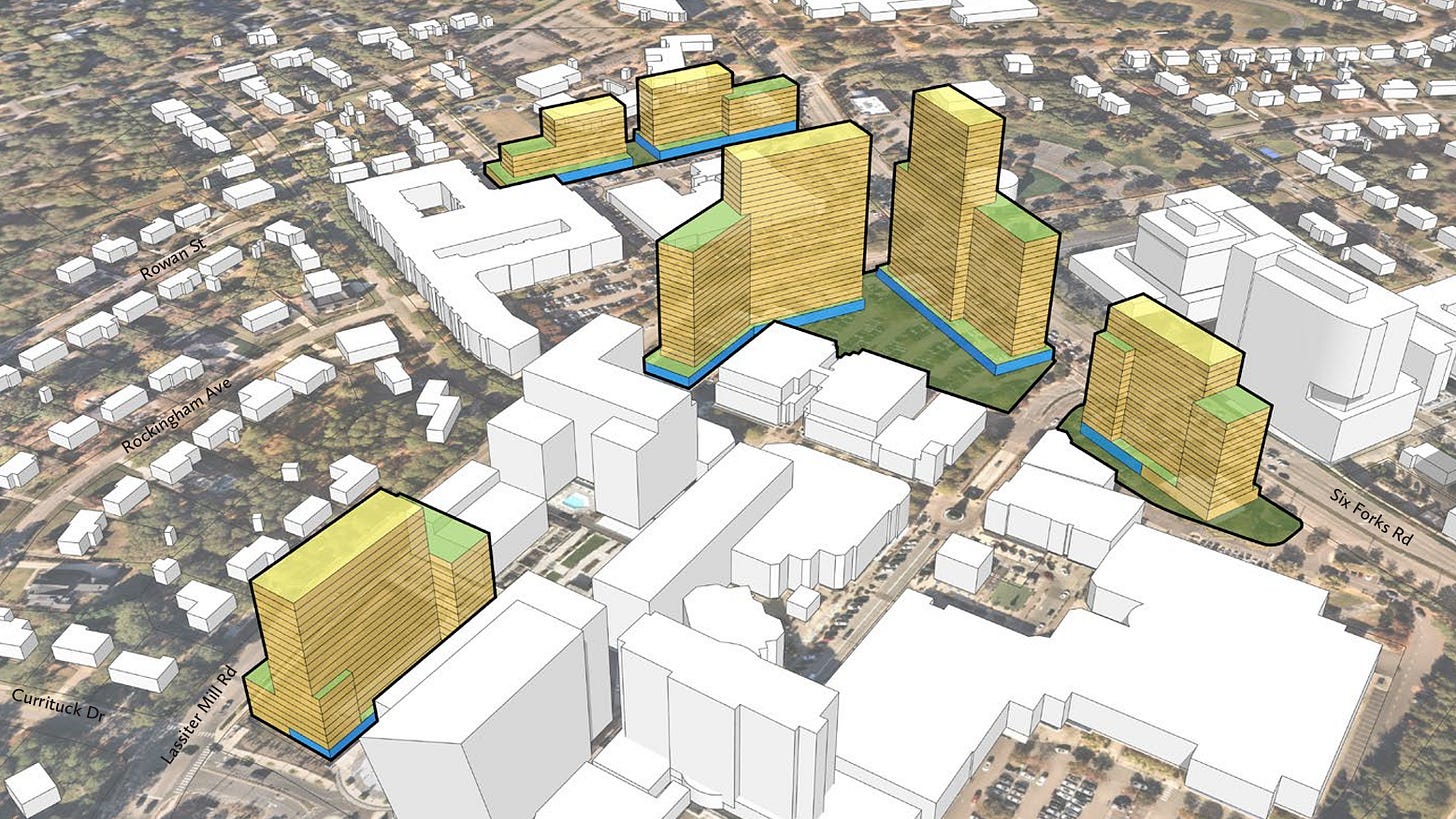

The current rezoning covers several underutilized portions of the site west of Six Forks Road. It would replace existing zoning with conditional‑use districts, allowing buildings between 12 and 37 stories tall. The proposal does increase allowable height, but it also places explicit caps on overall development. Limits on dwelling units, commercial square footage, office and medical space, and total building area are all written directly into the zoning conditions. In other words, it combines flexibility in building form with clear boundaries on what can ultimately be constructed.

In places like North Hills, height is often what makes mixed‑use projects feasible. Taller buildings allow for smaller footprints, larger public spaces, and the ability to actually realize housing capacity that already exists on paper. The rezoning also includes design and site requirements like stepbacks, limits on surface parking, new open space, green stormwater infrastructure, and green building standards. Including third‑party green building standards is a strong and welcome condition for tall building projects like this one, helping ensure that increased height also delivers better environmental performance.

Importantly, the City’s own planning staff found that the proposed entitlements would generate approximately 2,000 fewer vehicle trips per day than what is allowed under current zoning. That’s not just a talking point. It’s a reflection of how mixed‑use districts decrease traffic by enabling daily needs to exist within walking distance. The Planning Commission recommended approving the rezoning, with just one dissenting vote from Tolulope Omokaiye.

It’s also important to be clear about what this rezoning does not include.

Two years ago, a more ambitious North Hills proposal was being discussed. That version included room for a new fire station and land for a transit station that could have anchored significantly better public transit service into Midtown. That proposal never reached a public hearing. Political uncertainty, organized opposition, and a sense that approval was unlikely created enough doubt that the applicant withdrew. When the project stalled, those public benefits disappeared with it.

This is an insidious part of the development process that we see too often in the Triangle. Elected officials avoid naming it directly, but nonetheless: delay has consequences. Projects held in limbo do not quietly improve. Risk increases. Costs rise. Commitments shrink. If any developer could afford years of uncertainty, you’d think it would be the developer with the most experience and largest footprint in Raleigh. Yet, even they could not keep those elements on the table indefinitely.

The version before Council next week is still a good project. But it is more constrained than what was once proposed. Height has been reduced in some areas, overall density is capped more tightly, and ambition has been tempered by years of negotiation and shifting market conditions. Concentrating height at the core of the site, across from the Eastern (the existing 37‑story tower that has already defined the Midtown skyline for several years) is part of that tradeoff. When faced with delays, projects don’t get bolder; they get narrower.

There’s another tension in this case that’s worth addressing directly. In many rezonings, housing advocates argue for approval by pointing to Raleigh’s Comprehensive Plan. Here, the small area plan adopted in 2020 places height caps of roughly 12 to 20 stories across much of North Hills. This rezoning seeks to exceed those limits.

That doesn’t make the proposal reckless. It simply highlights a weakness in how small area plans are sometimes used politically. These plans often freeze a moment of political caution and treat it as permanent truth, limiting the ability of future councils and communities to respond when places evolve. The issue isn’t that conditions changed slowly over decades. It’s that the small area plan was already out of step with reality when it was approved. Plans should guide growth, not lock it in place. When an area demonstrates that it can support density and urban form, elected officials should have the flexibility to respond.

The opposition to this rezoning is familiar.

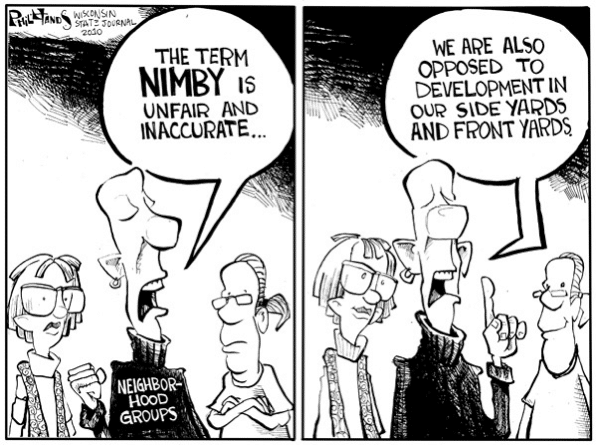

I’ve spent enough time in Raleigh City Council chambers to recognize the pattern. Many of the same voices arguing against this rezoning often proclaim that housing should be built near jobs, near services, and near existing infrastructure, while they oppose housing at the edge of the city in the name of fighting sprawl.

On that principle, I agree. The problem for them is that North Hills is that place.

North Hills, now grown up into a real Midtown, is a major employment center. It’s walkable. It sits right on the Beltline. It has long been identified as a future transit node. If mixed‑use buildings and new housing aren’t acceptable here, it’s hard to imagine where they would be.

At some point, this stops being a debate about location and becomes a question of whether we are willing to build at all. This is, quite literally, where the term NIMBY comes from: saying that housing and growth are fine in theory, just not in my specific neighborhood.

Delays and threats of denial rarely improve projects. More often, they narrow them, and public amenities are the first components to get the axe. Predictability, not posturing, is what allows cities to secure community benefits and plan for housing and transit over time. To this Council’s credit, expectations appear clearer than in the past. That clarity matters. Developers, neighborhoods, and transit agencies all plan around the signals that elected officials send.

So, why support Z-34-25?

Here’s the bottom line: Z‑34‑25 deserves support because it puts growth where it actually belongs. Adding density is good when it’s on underutilized commercial land, surrounded by jobs, services, and existing infrastructure, all in a place that has already proven it can function as a real urban center. It may not be perfect, but it is good.

City Council doesn’t get to vote on the project they wish existed. They get a yes‑or‑no vote on what has been proposed, negotiated, and brought forward. That makes this moment important.

If advocates want better outcomes, We have to say, clearly and publicly, what works and what should move forward. Supporting good projects is how cities get more of them.

This rezoning will be opposed by some. That is predictable. What’s less predictable is how many supporters of housing, walkable growth, and learning from past lessons will show up with the same clarity. We must.

If you believe Raleigh needs more housing choices and a planning system that rewards progress instead of punishing it, now is the time to say so.

The public hearing is January 6th. Speak for housing. Speak for learning from our past decisions. Tell Council that Raleigh became better once because someone was willing to imagine more than a parking lot.

We shouldn’t forget that lesson now.

🏙️ Z-34-25 PUBLIC HEARING | JANUARY 6

This is exactly where growth should go. If you agree:

📝 Sign up to speak at the public hearing

📨 Email your city councilor to voice your support

👥 Show up, even if you don’t speak

💚 Wear green to support the rezoning

✔️ Tell Council: North Hills is the right place to build tall

Opponents will be there. Supporters must be too.

Jenn Truman is a young designer, leader, and advocate based in Raleigh, she is embedded in the local community through both her professional and volunteer work. Jenn is a regular contributor to and Founder of CITYBUILDER.