Single-Stair Adds Homes Where Neighbors Want Them

Affordable housing can be created in the neighborhoods we already love

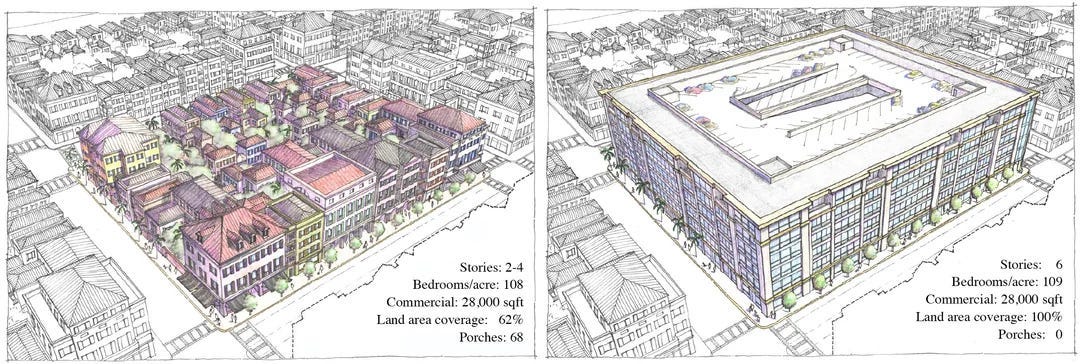

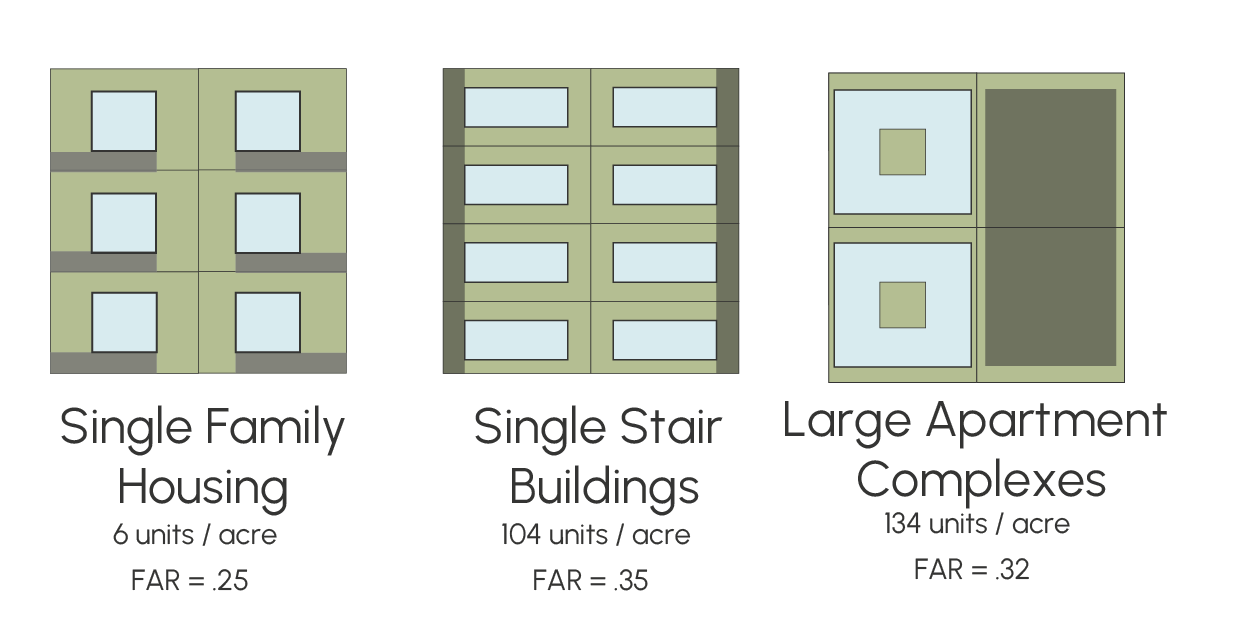

Right now, a historic amount of multifamily housing is being built across the U.S. According to the Institute for Family Studies, in 2024, over one-third of new housing units were in buildings with 20 or more units; the highest share since 1974. But not everyone is celebrating this development. Surrounding communities are often quick to push back on new multifamily housing with familiar refrains: “the density is too high”, “there’s too much traffic”, or “their size blocks out the sunlight”. But what if there was a way to let more people live in popular areas without the downsides of big apartment blocks and high-rises?

This piece was written by student fellows in collaboration with Single Stair NC. Each semester, CITYBUILDER provides fellowship opportunities for aspiring student urbanists in the Triangle. This semester we’re focused on single-stair apartments. Single Stair NC is a new publication committed to advancing the pursuit of single-stair buildings in North Carolina. Read more in this series:

When most people think about multifamily housing structures, the super tall towers of Miami or New York come to mind. Or maybe they’re haunted by the famous “Texas donut” buildings that seem to be popping up everywhere.

These massive structures often face pushback from local residents for altering the existing character of a neighborhood. But what if we could make multifamily buildings smaller? Thereby increasing housing supply while preserving communal fabric.

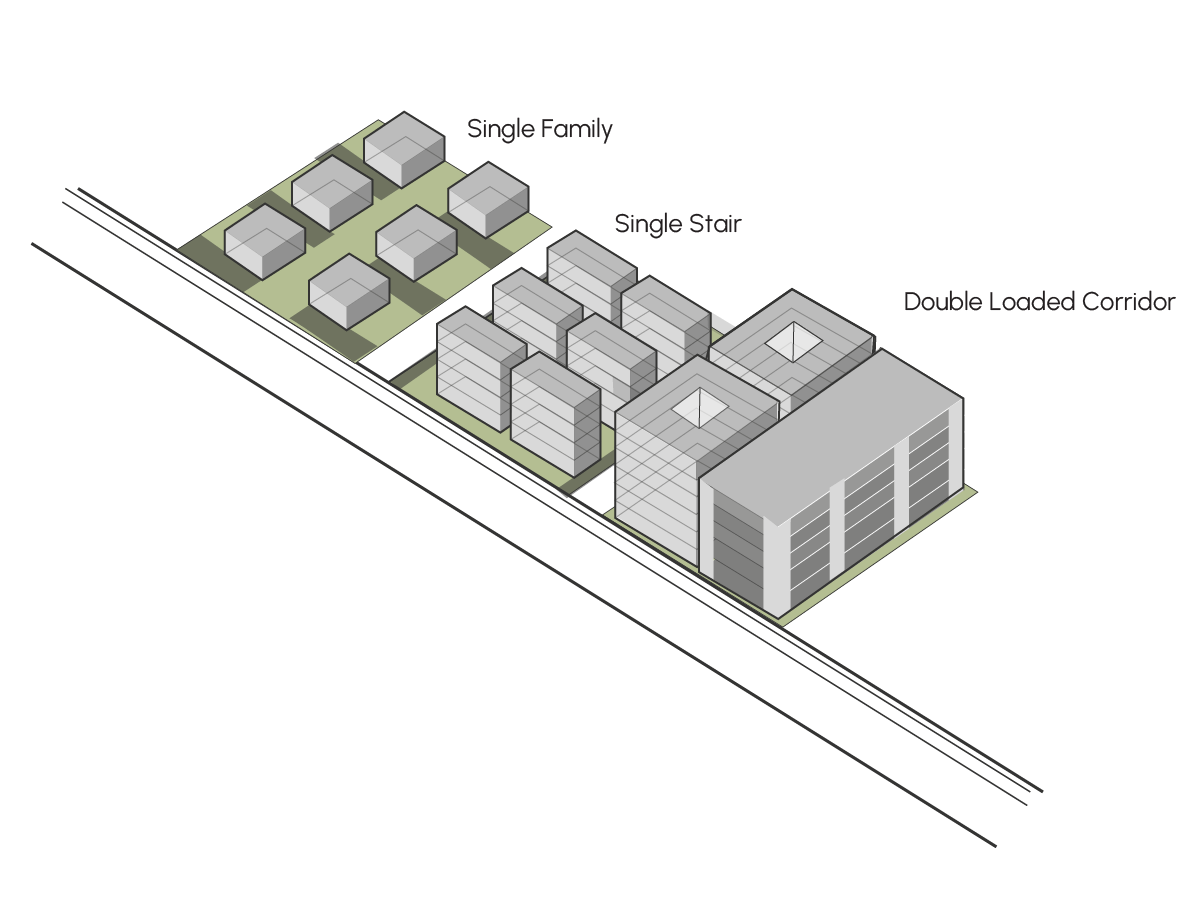

Single-stair apartment buildings allow us to do just that. By doing away with an unnecessary (though often legally mandated) second staircase, single-stair construction allows smaller buildings to be built on smaller lots, while maximizing the usable square footage within.

Single-stair structures are a comfortable middle ground for increasing housing availability and density in neighborhoods. Vacant suburban lots could be developed with single-stair apartment buildings, providing more housing per acre without dramatically disrupting the character of the neighborhood. We encourage you to check out LGA Architectural Partners, which explored some prototypes of single-stair buildings that would blend in with urban and suburban streetscapes alike.

Besides, the long corridors of large-scale apartment buildings aren’t just a pain to carry your groceries through, they also waste valuable resources in the construction process. Hallways are conditioned interior spaces used exclusively for movement to and from one’s apartment. Their presence in apartment buildings just doesn’t make sense when rentable square footage is such a hot commodity these days.

More Bedrooms for Your Buck

The cost of new construction is spread across the entirety of a building, meaning that each buyer or tenant is essentially paying for mostly empty spaces like hallways, vestibules, and corridors. Imagine if those hallways in a large-scale apartment building could instead be part of residents’ apartments.

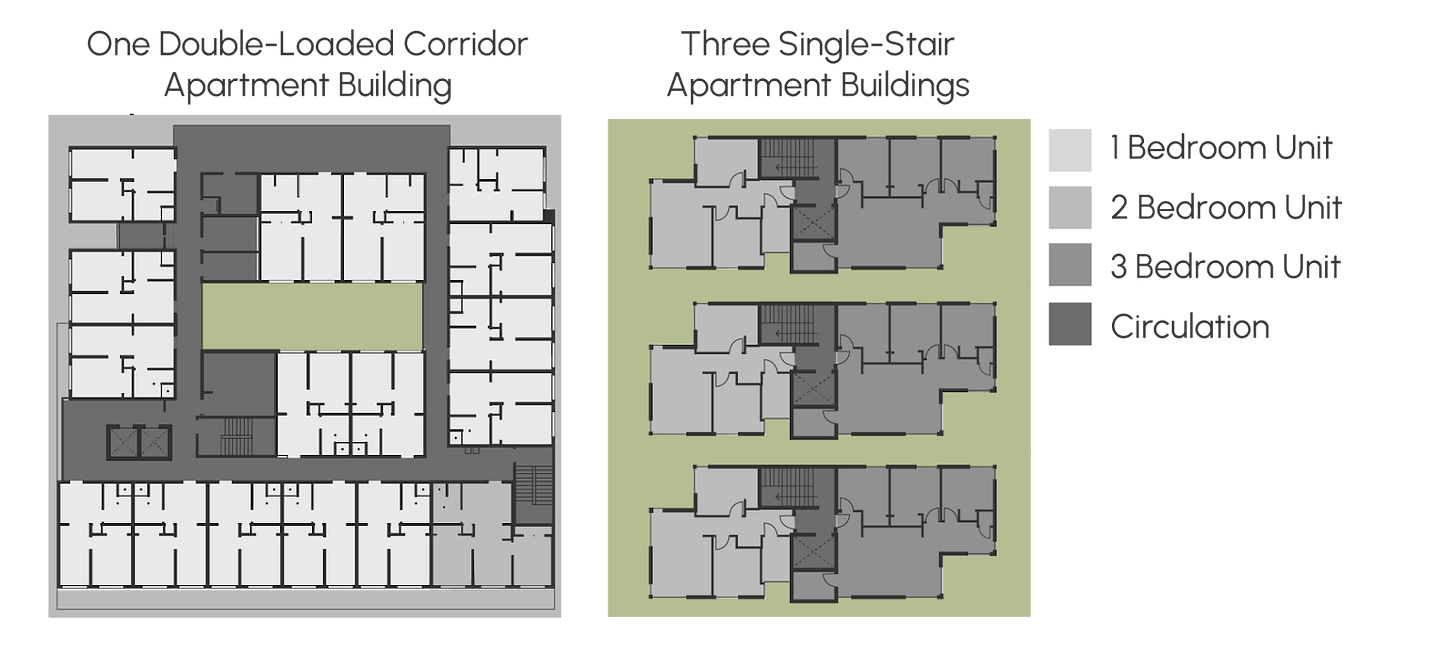

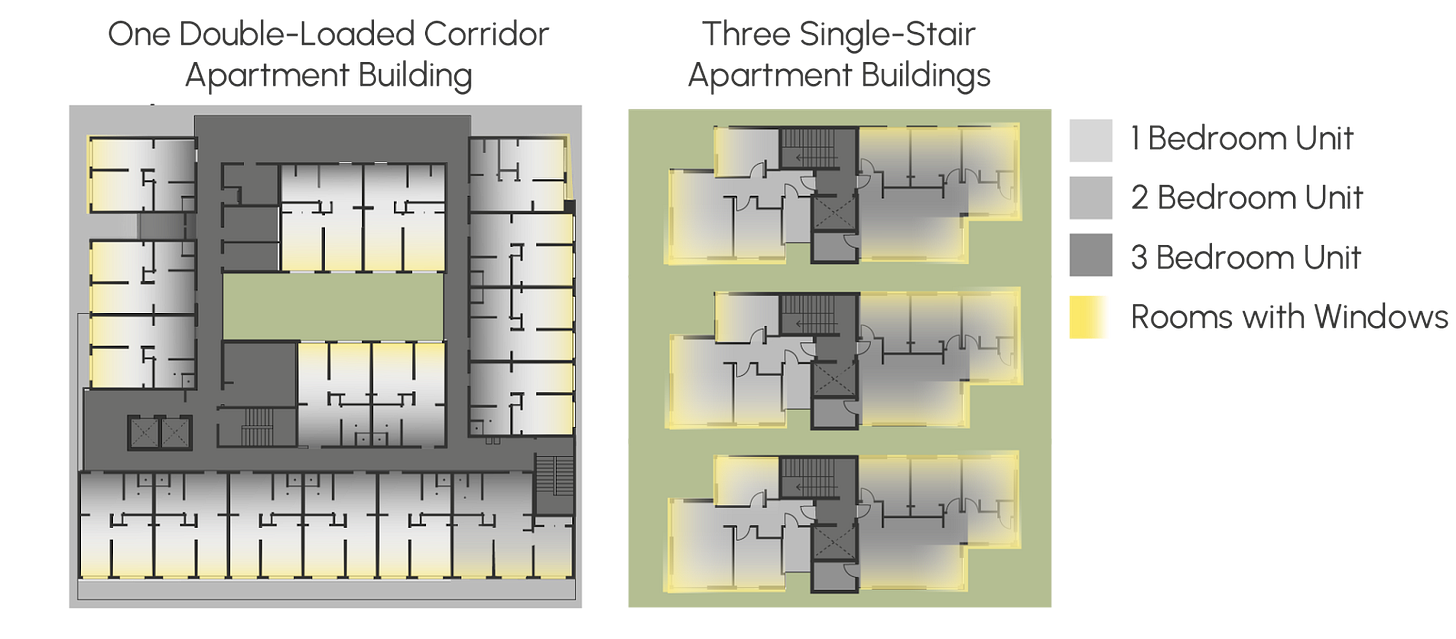

This is effectively what single-stair buildings do: they take a massive apartment building and divide it across multiple lots, each utilizing one staircase and elevator. Empty space previously taken up by long hallways is turned into rentable bedrooms. Additionally, all residential spaces are now higher-quality, receiving more direct sunlight due to the increased wall surface area of the building itself.

The single-stair advantage can be seen in a common planning metric: the “core-to-perimeter ratio”. This metric analyzes a building’s spatial efficiency by comparing its perimeter (or wall surface area) to how much space is taken up by utility and circulation (areas that aren’t lived in). A typical large apartment complex has a high core-to-perimeter ratio, owing to the sprawling interior corridors in the building. By comparison, single-stair structures consist of a few apartments arranged around a small utility core, giving them a low core-to-perimeter ratio. The increased wall length that each unit gains creates flexibility for window locations, providing natural daylight and cross ventilation.

Another metric where single-stair comes out on top is net-to-gross floor area ratio.

Gross floor area is the total floor area inside a building (including utilities, hallways, and stairways), while net floor area measures only the usable, liveable space within a building.

Single-stair buildings strike a balance of sharing utility systems and circulation space. By reducing the net-to-gross floor area ratio through the elimination of excessive corridors, tenants pay for less underused or empty space, and rent prices can likewise be reduced to better reflect the amount of liveable space.

Furthermore, the efficiency of single-stair structures allows more of them to be built in the first place. A developer designing a 4- to 6-story apartment building on a narrow urban lot might find that the cost of two stairways makes the project infeasible. The requirement of a second stair might force designers to use inefficient corridors, or resort to land aggregation (combining multiple lots). In turn, they may have to add more units to cover the increased costs.

This cycle can drive the scale of a project so large that it no longer fits (aesthetically or legally) into the surrounding neighborhood. By contrast, with a single stairway, the developer can build few enough units to make the project financially feasible on a smaller parcel. As a result, rent or sale costs can be lowered, while still delivering lots of usable space in each unit.

Let There Be Light (and Cheaper AC)

It turns out that illuminating, conditioning, and maintaining long, underutilized hallways is wasteful. Reducing corridor length and size means less wasted electricity and a smaller HVAC load. That translates directly to lower utility bills for residents. Also, having more natural light in units reduces the need for artificial lighting and heating within individual apartments.

Compared to large apartment blocks, lots with single-stair buildings contain more corners and walls exposed to open air. Current residential building codes require every room designated as a “bedroom” to have a window in it, primarily for safety purposes. Externally, single-stair buildings have larger perimeters and more walls exposed to open air, allowing each individual apartment unit to contain more rooms with access to windows, and thus, more bedrooms.

Single-stair buildings have an internal advantage too. Typically, the long corridors found in two-stair apartment structures divide the building into two, either with an inner and outer ring, or with two sides facing opposite each other. In both of these layouts, each unit can only have one wall facing outwards. This wall must contain all of the windows, and thus all of the bedrooms. This arrangement reduces the amount of natural light left for kitchen and living room spaces. By eliminating the need for a corridor that divides the building, units can span across several exterior walls of a single-stair development, enabling more naturally-lit living spaces.

Unlocking Greenery Through Gentle Density

One frequent objection to more housing is that it will overwhelm the look and feel of a neighborhood. Indeed, the introduction of a large-scale apartment complex often comes with the need for extensive parking directly adjacent to the structure, which can make it difficult to incorporate any of the development’s greenspace into the environment of the existing neighborhood.

In contrast, single-stair buildings encourage greenery through “gentle density”. They can be built at a scale compatible with existing blocks (two to four units per floor and four to six stories tall) instead of requiring massive “superblock” developments. Therefore, the greenspace on their lots can be more easily integrated into the fabric of surrounding homes and greenways.

Feasibility of Single Stair through Small-Scale Development

Because single-stair designs reduce complexity, materials, and wasted area, the up-front capital cost per unit tends to be lower. This means that small-scale or local developers (not just large, corporate developers) are more likely to find single-stair multifamily projects viable. This distributes opportunity more broadly, reduces reliance on “big developers,” and accelerates incremental infill development. When building large complexes is the only economically viable approach, many small lots remain underutilized or empty.

Legalizing single-stair buildings lowers the financial threshold, making small and medium-scale infill more attractive. If one old house in a neighborhood were up for sale, a local developer could turn that lot into several single-stair apartment units, rather than needing to buy out an entire neighborhood block to construct a large, two-stair housing complex. Allowing single-stair apartments enables neighbors to become developers, rather than national corporations.

All in all, the legalization of single-stair housing would provide a means of creating abundant low-cost rental units while preserving the character and feel of our favorite neighborhoods. Increasing density doesn’t have to be scary. With single-stair buildings, we can honor the neighborhoods of our present while constructing the communities of our future.

Julie Powers is a Bachelor of Architecture Student at NC State University, with a LAEP minor. Additional graphic and illustration support was provided by NC State Undergraduate College of Design in Architecture major Brenna Belcher.

Is the main obstacle fire code/egress?