The High Cost of Saying No

Five Points’ fight against housing diversity drives up prices for everyone — including residents themselves

Despite cooling housing costs across Raleigh, one cluster of neighborhoods stands out for refusing to budge: Five Points. Nestled inside the Beltline and steeped in historical charm, the area has become a hotbed of resistance to the city’s Missing Middle housing reforms. But here’s the twist: local residents’ opposition isn’t just hurting the city, it’s hurting themselves too.

This article digs into the story of Five Points, both as a group of neighborhoods and as a symbolic holdout against more affordable, inclusive housing in Raleigh. We’ll explore the history, the lawsuits, the zoning fights, and the costs — financial and otherwise — of saying “no” to change.

Five Points Defined

The Five Points area is a cluster of five historic neighborhoods, the core of which includes Hayes Barton, Bloomsbury, Vanguard Park, Roanoke Park, and Georgetown. The leafy, sidewalk-lined streets were among Raleigh’s first white suburban expansions, developed in the early 20th century around the now-defunct Glenwood streetcar line.

To attract interest in these areas, Carolina Power & Light opened Bloomsbury Park in 1918, complete with a roller coaster, arcade, and carousel — all lit by then relatively rare electric lights. As families flocked to ride the streetcar and visit the park, they were also shown nearby real estate that was marketed aggressively to the city's white middle- and upper-middle-class buyers.

In more recent years, Five Points has come to represent something other than family fun: the deeply entrenched resistance of older, wealthier, and predominantly white residents to housing changes that could allow working-class and younger people — many of them renters or people of color — to move closer to better jobs, schools, and amenities. This is NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) in action, with a twist of exclusivity baked in by both history and policy.

From racially restrictive covenants of the past to today’s “neighborhood character” arguments, the story of Five Points is a case study in exclusion through zoning.

How They’re Fighting Housing Diversity Today

The battle lines are clear. Raleigh’s Missing Middle Housing text amendment, which passed in stages between 2021 and 2022, legalized duplexes, triplexes, townhomes, and ADUs (Accessory Dwelling Units) across much of the city, including in low-density residential zones. Advocates and academics alike recognized the reforms as a critical step in expanding housing options for the growing city.

But in Five Points, the backlash was swift and fierce. When a project proposing 18 townhomes at 908 Williamson Drive was approved, residents of Hayes Barton filed a lawsuit seeking to overturn the Missing Middle ordinances entirely. Their argument? That the reforms were illegal zoning map changes, not text amendments, meaning Raleigh had failed to provide the required mailed notices to homeowners.

This legal action followed years of opposition to development in the form of protests and speeches at city council meetings, often dressed in the language of preservation. Rules governing the area’s Historic Overlay District create design review processes that limit what can be built and how. Changes to exterior materials, additions, and new constructions all face strict scrutiny. In theory, these rules protect history. In practice, they often block new homes, particularly those that don’t fit the existing single-family mold.

But They’re Losing Either Way

The irony is that Five Points suffers from the status quo it’s fighting to keep.

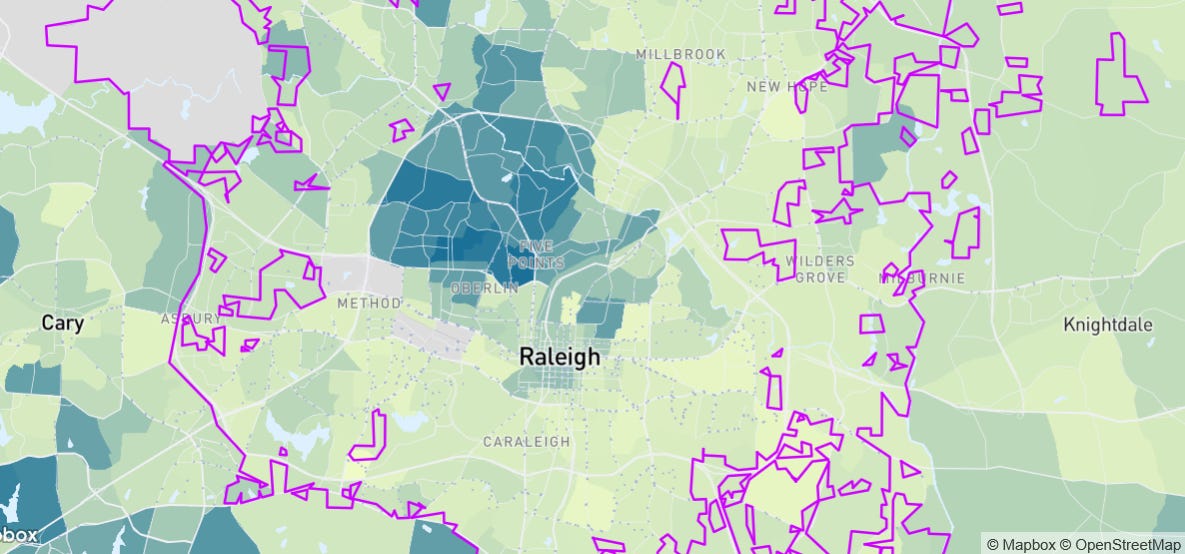

This graphic, pulled from the Housing and Transportation Index, displays housing affordability in Raleigh. The darker an area appears on the map, the larger the share of residents’ incomes spent on housing costs — rents, mortgage payments, property taxes, insurance, utilities, and building fees.

As the index clearly shows, Five Points residents spend the highest percentage of their income on housing of any neighborhood in Raleigh. In short, the community is one of the least affordable for its own residents — the systems they are fighting to preserve are costing them dearly. Missing Middle housing could make neighborhoods like Hayes Barton more affordable for existing and future residents alike.

In court, the resistance of Five Points residents has been shaky. After initial setbacks, the developer of the Williamson Drive townhomes amended the project’s plan and obtained re-approval from the city in early 2025. Hayes Barton neighbors could appeal again, but legal experts say the odds of success are slim. CITYBUILDER covered the legal basis of litigation against Raleigh’s Missing Middle housing back in May, and you can read up on Missing Middle projects that are currently underway here. Even as the lawsuit drags on, construction of the townhomes is likely to begin soon; the actual development will move forward.

Meanwhile, it’s becoming clear that a de facto development moratorium in a wealthy historic neighborhood near downtown pushes teardowns and development into less affluent and historically marginalized neighborhoods. Just as Raleigh residents share the pains and pleasures of living in a growing city, so too should neighborhoods share the burden — and benefits — of change and growth across socioeconomic lines.

How We Can Actually Lower Housing Costs

Change can be uncomfortable. But Raleigh is changing whether Five Points likes it or not.

Durham and Raleigh have both passed sweeping zoning reforms to allow more housing types, and many smaller Triangle municipalities are now considering or implementing reforms that prioritize inventory over exclusivity.

Here’s the truth: there are two ways to lower housing prices.

Subsidize housing — hard, expensive, and politically difficult.

Build more housing — doable, effective, and already happening.

At CITYBUILDER, we’re proudly on Team Build. We believe the best way to ensure a livable, affordable Raleigh is by making room for more neighbors. We know our opponents will reap the benefits even as they protest.

New builds are often more expensive than older, naturally affordable housing, but increasing the supply of new units makes housing more affordable overall. In short: the more homes that get built, the more affordable housing becomes.

We’re building a city that works for everyone. That means more homes, more choices, and more opportunity. The fight for the Missing Middle isn’t just about zoning codes; it’s about fairness, affordability, and the kind of future we want. Whether or not neighborhoods like Five Points think they’re ready, change is coming — and we’ll keep pushing to build more homes.

Kyaira Boughton is a visiting student from Duke Kunshan University, pursuing a dual degree in Computation and Design with a focus on Social Policy. With expertise in GIS, 3D modeling, and urban policy, Kyaira combines technical and social insights to effectively analyze and communicate complex urban design concepts.