We Support a ‘Baseball First’ Policy

Whether through renovation or a City League, Durham must put hardball at the center of its pitch.

This is Part III of a series on baseball and placemaking, focused on the history and redevelopment of the Durham Athletic Park. Part I explored the early history of the ballpark, and why it still matters today. Part II explored how the park is currently used.

Baseball doesn’t need reinvention — it needs reaffirmation.

In downtown Durham, where warehouses have become food halls and factories now host tech startups, the Durham Athletic Park (DAP) remains one of the last pieces of urban fabric still doing the thing it was built for. That continuity matters. As the city weighs the future of this field, the next phase of development shouldn’t treat baseball as an afterthought — it should put the game first.

A City League Is Worth Believing In

Picture this: A Saturday in the spring. A new Carolina City League game between Durham and Raleigh is underway. Kids are playing catch in the grass berm. Food trucks are lined up outside the gate. Families and college students stroll over from nearby apartments to catch the last couple of innings; half of them sport kitschy jerseys of their local team. The stadium is buzzing — not with memory, but with life.

There’s no reason this can’t be our future.

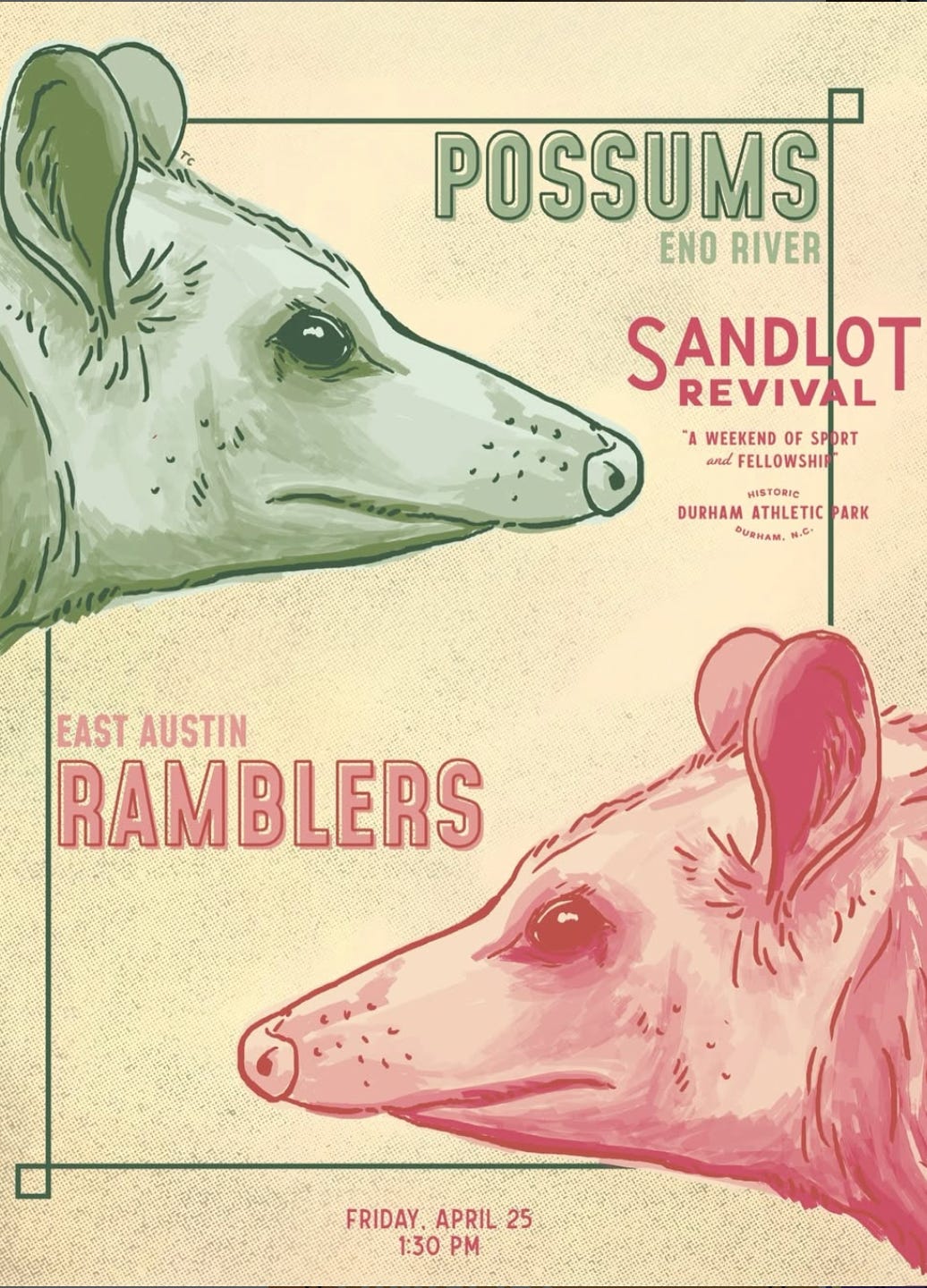

A future Carolina City League, like the existing Carolina Sandlot Collective, isn’t about perfect fields or polished uniforms; it’s about showing up as a community. It’s about teenagers dragging rakes across the infield, dads keeping score in spiral notebooks, and dogs asleep in the shade of the backstop. It’s about mismatched socks, walk-up songs played from a Bluetooth speaker, and someone’s grandma cheering louder than anyone else. At its core, sandlot baseball is localism in action: community-built, community-led, and full of pride. These games aren’t just recreational — they’re ritualistic, stitched together by a love for the sport that doesn’t fade with age.

That localism is what makes the Carolina City League more than a possibility; it’s a natural next step. The Carolina Sandlot Collective shows what’s possible with grit and community; a formal intercity league could elevate it with structure and statewide celebration. Merch would fly. Rivalries would grow. It’s grassroots baseball at a regional scale, where pride of place meets the joy of play.

This spirit cuts across generations. We envision a Durham Cup — an annual high school and even middle school Durham City Title series, where alumni can cheer on their alma maters, buy jerseys, and bring their history forward into a new future, where local pride is expressed through grassroots sport.

We imagine development that includes apartments, yes — but ones that face the outfield and integrate with the park. This isn’t fantasy. It’s good urbanism rooted in community, memory, and play.

What Does “Highest and Best Use” Really Mean?

Looking forward, we are obligated to ask ourselves, “What goes best on this land?”

If we’re just asking an Excel-driven MBA what should go here, the answer is easy: apartments. But this isn’t just a spreadsheet problem. It’s a story problem. Because baseball doesn’t compute the way square footage does, it’s not quantifiable — it’s emotional, symbolic, and shared.

In Microsoft Excel, the value of local baseball is zero. But in some of our hearts, it’s incalculable.

Baseball is a game, yes. But it’s also a kind of secular religion. A wood bat cracking against a ball under spring skies triggers something primal. That’s not a use, that’s meaning. And at the DAP, meaning matters more than profit margins.

A Cautionary Past

Durham’s current feasibility study, led by Perkins & Will, seeks to chart a course forward for the DAP. But many in the community remember what happened last time the city hired a big-name consultant: Skanska replaced the iconic faded-paint plywood outfield wall with a chain-link fence. Nothing could be less historical or less honoring of the tradition.

The modern world is sterile. That chain-link fence in the outfield makes the DAP look no different than the fields at Valley Springs Park or any suburban high school in the Triangle. Those are fine, but they’re not special.

Minor league parks are special because of how local they are. Why not lean into that?

Bring back hand-painted ads for Durham businesses. This need not be hard: “Hit Bull, Win Cocoa Cinnamon’s Cortadito Cubano. Hit Grass, Win Geer Street Garden’s Fried Chicken Salad.”

Better yet, paint them on sun-faded, rotting plywood like they used to be — imperfect, alive, and unmistakably ours. That’s not just romanticism of the past. That’s authenticity.

What the Bulls’ Community Is Saying

Baseball lifers like Miles Wolff, the former Bulls owner, see the stakes clearly. “It just has the feel of a good old minor league ballpark,” he said. “I hope the city doesn’t tear it down.”

Durham City Council member Carl Rist says he “has many memories tied to the DAP — from watching Bulls games when they played there, to attending the Bull Durham Blues Festival many summers, to even playing there in an adult league.” For him, “the field isn’t just a nostalgic backdrop, it’s a space that helped shape Durham’s identity.”

The takeaway? This isn’t just a piece of land; it’s a significant piece of the city’s story.

Mike Birling, Durham Bulls vice president, sees flexibility as key to the DAP’s future. “I would like to see the field turfed so we are able to activate the stadium in many ways beyond baseball,” he said. “Could be soccer, could be concerts.” For Birling, preserving the spirit of the ballpark doesn’t mean limiting its use; it means adapting it to serve more people, more often.

Preservation Through Modernization

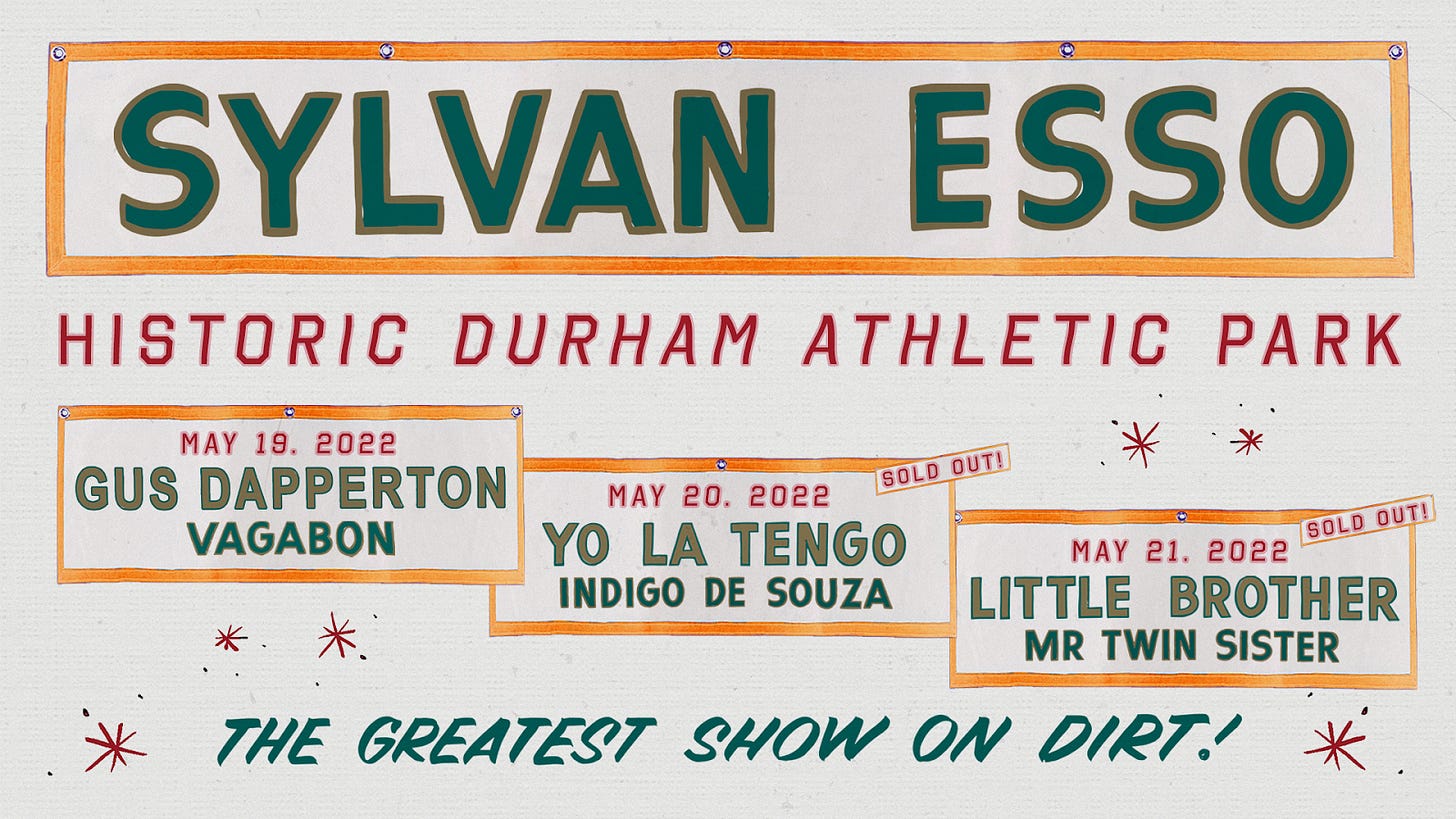

Preservation doesn’t mean stagnation — it means evolution. There are exciting, viable ways to modernize the DAP while keeping baseball at the center. Imagine improved concessions, better lighting, flexible seating, and a modest field house that doubles as community space. Festivals, concerts, and touring groups like Sylvan Esso can continue to thrive in tandem with the game.

As Durham’s Central Park district continues to grow, the Durham Athletic Park can be a true gathering place for the community. To make that happen, the park should stay rooted in baseball while also becoming a flexible space that reflects the energy and diversity of our city. Here are a few simple ideas to help get there:

Stronger neighborhood connections

Create a new pedestrian entrance on Corporation Street and a dedicated bike path linking the DAP to the Durham Rail Trail. Widen sidewalks along Washington and open up sightlines to nearby businesses so the park feels like part of the street, not separate from it.Everyday use for everyone

Convert the grass berm between the field and concessions into a shaded hangout space with benches, picnic tables, and lights. Open the gates a few mornings for “Walk the Bases” hours, or let local youth teams host pickup games on weekday afternoons.Programs with local partners

Work with Durham Public Schools to host student showcases or science nights themed around baseball stats and physics.Creative community performances

Set up a small stage on the third base concourse for Friday night performances — spoken word, jazz quartets, youth dance crews. Partner with NCCU or the Hayti Heritage Center to run storytelling events that honor Durham’s Black baseball and civil rights history. Better yet, use these events as a way for the greater Durham community to come together to put NCCU’s baseball team back on the field.

These ideas don’t take away from baseball or from the city. They build on what the DAP already means to Durham.

But It Must Be Baseball

Things change. Tobacco warehouses no longer need to process tobacco. But the DAP still has a job to do. It holds memories. It hosts joy. It tells a story that no other field in the country can. It’s the most famous minor league baseball stadium on Earth.

To turn it into just another patch of apartments would be to give up on something irreplaceable. You can’t rebuild this kind of meaning once it’s gone.

This isn’t about resisting growth. It’s about guiding growth with intention. Durham is a national model for integrating baseball and urbanism. The DAP is proof. The nearby Durham Bulls Athletic Park (DBAP) is further validation. It’s who we are. We shouldn’t waste that legacy. We should build on it.

Keep it a ballpark. Build around the game.

Make it better, more inclusive, and more alive.

But never, ever tell baseball to leave.

Over this series, we’ve looked at the history of the Durham Athletic Park and explore how Durham might continue this legacy while meeting modern needs. Check out Part I and Part II to read more about a place where baseball lives, memory endures, and the city still comes together.

Levent Goknar is the James Hardie Fellow for Urban Development. He is a Durham native and student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. As a left-handed pitcher, he played four years for the Durham School of the Arts baseball team, where he remains the all-time strikeout leader for the school, whose home field was the DAP.